Law Offices of John P. Connell, P.C.: In Massachusetts, pursuant to state law, the number of liquor licenses towns and cities are authorized to issue is capped at a certain number based upon that municipality’s population. Essentially, the law provides that one all alcoholic beverages pouring license may be issued for every thousand people in that municipality.

Yet, not all cities are subject to the current quota system. Over the years, since the repeal of Prohibition, up to twenty-five municipalities in Massachusetts, including Cambridge, have been authorized to opt-out of the current quota system and issue as many licenses as the municipality sees fit. Many of those municipalities, however, have imposed their own “informal” caps. For example, the city of Cambridge requires an applicant seeking a new liquor license to demonstrate that it has already tried and failed to purchase an existing license. In addition, there remain many municipalities that are subject to the quota system, which have not issued all the licenses available to that town or city simply because of the non-interest of prospective restaurateurs.

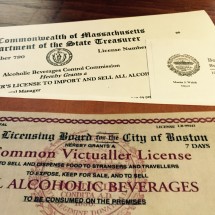

With regard to the remaining municipalities that are subject to the quota system, and which have reached their quota of available licenses, such as Boston, in order to enter into the market a prospective restaurateur needs to purchase a liquor license from an existing restaurant and that restaurant location will either be operated by a new owner or the license will be moved to a new location and the old restaurant will either cease doing business or continue on without a liquor license. In these municipalities, therefore, a liquor license is highly valued; particularly in Boston, a liquor license can cost as much as $400,000.00 or more.

Indeed, most restaurants that lease space in Boston consider their liquor license as their most valuable asset – far ahead of good will, furnishings and equipment. That singular asset with a discernable and transferable value has therefore not only acted as a hedge against over competition in a particular market for the potential buyer of a restaurant, but also as an asset that banks have grown comfortable with using as collateral for loans to potential restaurant buyers. Existing restaurants that purchased their licenses years ago value the potential re-sale of their businesses based upon this fixed asset. People who have invested money into restaurant businesses over the years did so with an understanding that the existing liquor license was highly valued due to a quota system that has gone unchanged for more than eighty years.

In short, the economics of the restaurant industry subject to the quota system – and a lot of people’s financial investments in that industry – are premised on a valuation of a common asset that everyone has come to know and be comfortable with. Municipalities that have reached their quota of available licenses and which are finding a demand for more licenses, and want to see new restaurants open within their borders, have routinely sought a certain number of additional licenses from the state through a complicated home rule legislative process. This process of adding a measured amount of licenses to meet demand has thus far seemed to relieve some of the steam currently overheating the new restaurant resurgence in Massachusetts.

Now, however, in the name of economic stimulation, governmental forces are seeking to wipe out the quota system altogether and devalue the price of a liquor license. On May 13, 2014, Governor Deval Patrick announced that he would support state legislation that would eliminate this current statewide quota system and allow each city and town to decide for itself the number of licenses it may issue. The Governor enjoys broad support for his proposal to eliminate the liquor license quota system in Massachusetts and has received the backing of Mayor Marty Walsh of Boston as well as a great number of the mayors and boards of selectmen from across Massachusetts.

Indeed, there is a compelling argument that an increase in the availability of liquor licenses to would-be restaurateurs will result in an increase in the amount of restaurants, and with these new restaurants will come the gentrification, real estate development and revitalization of areas that were not previously in demand. Proponents of this argument point out that, in Boston, for example, new restaurants like Del Friscos and those at Liberty Wharf have revitalized larger areas such as the Seaport, and new restaurants like The Ledge Restaurant in Lower Mills have revitalized small neighborhoods in Dorchester. Boston City Councilor Ayanna Pressley, a leading proponent of the effort to dismantle the quota system, has specifically maintained that when The Ledge Restaurant arrived on Dorchester Avenue in Lower Mills several years ago, the people of the neighborhood found a new sense of community in the new establishment. Ms. Pressley stated is quoted as saying, that: “The Ledge came to Dorchester Avenue right in Lower Mills six years ago. There was a lot of controversy – people didn’t want it there. It revitalized the neighborhood at night. It brought people to town who then went to different places. People started extending their hours because they felt more comfortable in the area. It had a very positive impact.”

Proponents of this argument to expand the number of available liquor licenses, however, do not concede that these areas of recent development and gentrification, as exhibited by their attendant new restaurants, have simply replaced tired old restaurants with new restaurants and acquired no new liquor licenses within that neighborhood. Indeed, new restaurants in the Seaport have replaced such iconic establishments as Jimmy’s Harborside and Anthony’s Pier Four which sat for decades in an area of Boston that saw little economic development. The Ledge in Lower Mills simply replaced Donovan’s Pub, a dark and tired old neighborhood bar that served the same alcoholic beverages The Ledge served when it acquired its liquor license but did so in a more friendly and well-lit atmosphere.

Other such success stories in Boston such as City Square in Charlestown or Broadway Station in South Boston have seen great economic development in the past fifteen years with actually fewer overall licensed establishments located in those neighborhoods. The difference being the presence of one or more “high end” or “new concept” restaurants where tired, old establishments have lost their appeal, rather than an overall increase of new licensed establishments. Olives in City Square, Charlestown was largely associated with the revitalization of that neighborhood in the early 1990’s, for example, but there was a time in the 1940’s and 1950’s that Charlestown was known to have the most licensed establishments per square mile anywhere in the world, which only caused developmental stagnation.

All of the success stories in Boston and other Massachusetts communities where economic development has taken root, attribute their success to a variety of other factors that have garnered positive change in a particular area, including private investment in housing and shopping developments; governmental improvement of infrastructure or accessibility to public transportation; and accessibility to a job market that improves upon the job market that stood before. New restaurants of any quality that arise in a previously blighted area have not yet proven to be a generator for larger economic growth alone.

In other words, the quantity of liquor licenses is not the obstacle to economic development in Boston; rather, the quality of restaurants utilizing those liquor licenses is both a degenerative and positive aspect to such development. There is simply no evidence to support the broader argument that if municipalities had an unlimited amount of liquor licenses, such licenses could be strategically issued to stimulate economic growth. There is only one sure consequence of eliminating the current quota system in Massachusetts, and that is that liquor licenses that now have a relatively certain value will be worth a lot less, if anything, without some careful planning and legislating to protect these values.

The consequences of this devaluation are hardly certain and will most likely be unexpected. For instance, millions of dollars collateralized by essentially only liquor licenses is on loan from commercial banks in Massachusetts to restaurant owners who financed the purchase of their restaurant or borrowed money for its operation. Yet, a devaluation of that collateral will require restaurant owners to either pay off those loans or substitute collateral if they can.

While the current quota system can be argued to be an entry barrier for the Massachusetts restaurant business, in the past that limitation too has provided stability to an already competitive businesses attracting a finite amount of restaurant-going patrons, and has established the standard by which these businesses are operated to rise as well. Providing food to the public, adhering to the health and building codes, and properly abiding by the high standards required of those providing intoxicating beverages, are all serious obligations not to be undertaken by those who are un-capitalized or not financed well enough to spend money on compliance related issues.

While the current shortage of liquor licenses in some cities and towns has caused many local, smaller neighborhood bars to be essentially a thing of the past, so too in these same cities and towns have bars that once catered to drug dealing, gambling and other elicit crimes become a thing of the past. These “gin-mills” or “buckets of blood” were once very common in the metropolitan Boston area and they appear in most local notable crime dramas, both real and fictional, but they are mostly gone or almost entirely on their way out. Liquor licenses have simply become too valuable an asset for them to be left to a dark and dingy “gin-mill” with no significant business other than serving those who used the establishment as a cover to sell drugs or engage in another criminality. Liquor licenses have certainly become too valuable an asset to existing establishments to run the risk of losing its license to regulators if criminal conduct is allowed to exist on its premises. In short, it can be argued that a shortage of liquor licenses has simply driven the criminal element out of bars and caused the quality of service to increase.

Making the number of new liquor licenses available to anyone who wants to apply for such a license, it seems, will have consequences that may not be fully comprehended, and like with most proposed legislation designed solely to stimulate economic growth – rather than remedy an actual public need – its consequences may have effects that the state, cities and towns have not fully appreciated. One would hope there is significant more public debate on this issue before Governor Patrick gets too far down this road to reform.

© 2014, Law Offices of John P. Connell, P.C.